Behzad Kateli, Liddy Nevile,

La Trobe University, Australia

The shift from a techno-centric approach to a user-centric approach in the creation of websites encourages website authors to create content that is usable and accessible to all users. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has developed technologies to ensure that Web content can be accessible to people with special needs and preferences. This paper will concentrate on annotation of Web content as a strategy for increasing accessibility. Amaya and Annotea, two W3C software tools, are used by the authors to enhance access to information-rich content. Scenarios demonstrate different user situations and show how Amaya, a browser/editor, can be used to make annotations to enhance the experience of users with special needs/preferences. The annotations are stored and made available by Annotea.

Accessibility, Semantic Web, user experience, Annotea, Amaya, needs and preferences

Sir Tim Berners-Lee claims "The power of the Web is in its universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect" [1]. The number of websites with accessibility services for resource information is growing slowly; sadly, and this is particularly true of websites of Australian institutions such as universities and museums. This, in a context where the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2003 survey of disabilities showed that 1 in 5 Australians (3,958,300 or 20%) had reported a disability [2]. Providing information as accessible content is no longer an optional feature but a legal requirement [3].

Accessibility, in this paper, is a term used to refer to the matching of resources to users' needs and preferences. In other contexts, this means users finding versions of content in appropriate form and modalities, according to their needs and preferences. This is considered to be fundamental to accessibility. What is described here is additional to that and may, in some cases, offer more to users than just providing for their basic needs.

One method of providing individuals with meaningful experiences is through the use of annotations. Annotations, in this case, are comments, notes, and additional external information that can be attached to a Web document without having to change its original state [4]. People other than the original authors can change, interpret or add viewpoints or arguments to existing materials and, in the process, personalise them to suit the need(s) of an individual person.

For example, consider Mary, a secondary school teacher teaching science. She will direct her students to an on-line website which contains information for their upcoming assignment. but she is concerned that Peter may have trouble comprehending the information due to a vision impairment. Currently the website has a number of sections which contain both text and images: the text is encoded so as not to be suitably tranformable for Peter and the images are too small. The website has no features/services to accommodate for Peter's situation. Mary uses Annotea to make an augmented version of the web pages with larger, clearer text and descriptions of the images. Now Mary's students can use the original resource and Peter has the option of viewing the annotated version.

(The later parts of this paper show how this can be achieved step-by-step by a user who has Amaya as a browser and an Annotea server.)

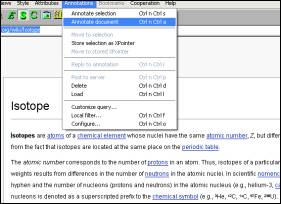

Amaya is a W3C web browser which doubles as an authoring tool. It is, in fact, W3C's demonstration browser that is made as standards compliant as possible. It supports many emerging and accessible Web technologies such as XML, (X)HTML, SVG, MathML, CSS, XSLT and others [5]. It includes a client implementation tool for creating annotations. Using Amaya, a user can create a new document or edit an existing document/resource.

Amaya is the result of an open source project. Distribution of version 8.6 (the latestat the time of writing) is available for a number of platforms including Windows, Mac and Linux. Installation setup files and installation instructions are obtainable from the Amaya website (http://www.w3.org/Amaya/User/BinDist.html).

Annotea is an open source Web server that uses Resource Description Framework (RDF) to describe annotations of resources. This means that an original webpage, stored and served from location X, can be altered and the alterations stored on the Annotea server so that if the page is retrieved from the original source on a second occasion, it will not be changed, but if it is retrieved from the Annotea server, it will include the changes.

All information concerning installation and configuration of Annotea can be obtained from the Annotea website (http://www.w3.org/2001/Annotea/User/Installserver.html).

Although this paper will concentrate on using Amaya and Annotea for creating content via annotations for people with special needs/preferences, other annotation tools exist such as; Annozilla, which is an Annotea implementation for the Mozilla browser [6]; Annogates, an Annotea client for Internet Explorer [7]; Zope, an annotation server based on the Annotea Protocol [8]. The Semantic Web Accessibility Platform (SWAP) is enterprise software that allows a user to achieve greater accessibility by changing the original state of a resource [9]. This paper shows how this can be achieved through freely available tools.

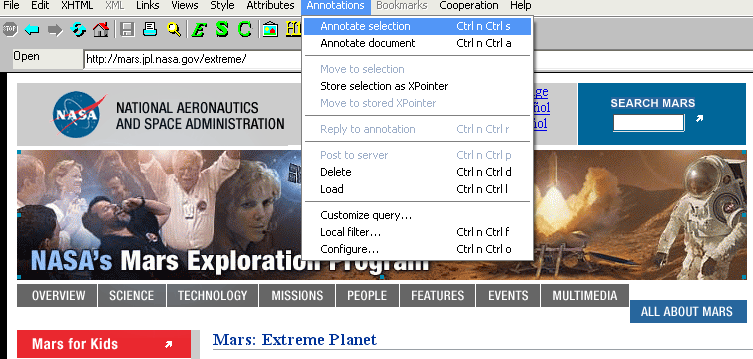

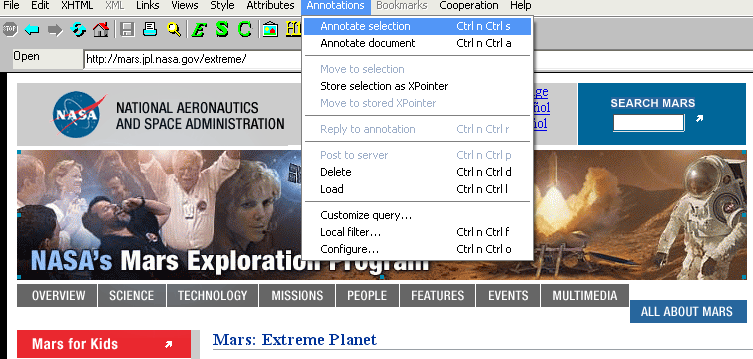

Continuing the example given earlier, Mary now uses Amaya to annotate an on-line resource about Mars. Many websites contain elements which can be inaccessible to a user. For example, at times users are not be able to view images. In some cases, the information contained in the image is crucial to their understanding of the rest of the content.. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines [10] specify techniques for making non-textual content (i.e. images, audio, video) accessible for such people. Mary uses Amaya to annotate the images and include alternate text and even long descriptions.

Alternatively, as images can be more helpful to people with dyslexia, annotations that consist of of images or icons can be added to replace text to make Web content more accessible. Mary could have substituted for some of the text by providing appropriate images where suitable.

Rebecca is an international student from Greece visiting an Australian university on a student exchange program. She is a little worried that she will not be able to understand her course materials as her English literacy is very limited. Being a good student, she enquires whether the university can provide some of the subject material in Greek. John, a lecturer in the business department, is familiar with the problem as it applies to many international guests who visit the university. He advises his information technology department of Rebecca's needs but they do not have the resources to provide multiple language versions for individuals who are visiting for a short time.

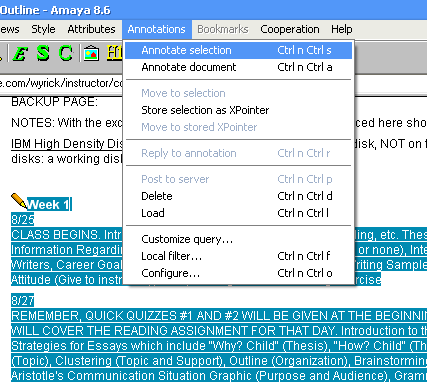

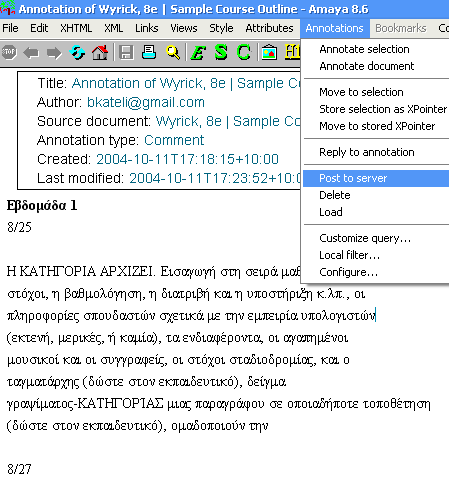

John hears of Amaya from a work colleague and decides to use its annotation feature to annotate some course information to help Rebecca. John, unable to read or write Greek, seeks help from the university's language department who happily check the translations that he makes using Babel Fish [11].

John, now having the translation, uses Amaya to create an annotation1

for the original on-line material (Example 2-3).

In a paper for Museums and the Web 2004, Nevile et al. (2004) describe an educational scenario based on a student by the name of Maria. The following is a brief summary:

Maria's case is not unique. Many people may suffer from disabilities that can effect the way they learn and comprehend information. In this paper, we choose to think about the disability dyslexia because it is invisible and yet common in institutions of higher learning. We note that people with dyslexia do not always want to inform others of their problem but generally want to participate in the same activities as others.

Dyslexia Parent (http://www.dyslexia-parent.com/) describes some useful principles for on-line content:

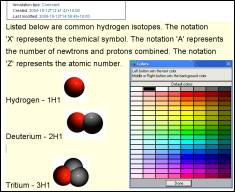

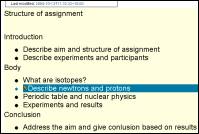

How can John Zimmer create an annotation for Maria while addressing some of the issues above? Let's annotate a physics page on isotopes.

The annotation shown above features a number of elements that John added to enhance Maria's learning experience. First, John simplified the text using Helvetica as a clear and understandable font and increased its size. Selecting 'colors' from the style menu, John chose background colour '#FFFFE5' as recommended by Parent-Dyslexia.com [14], sentences were kept short to enhance readability. Images were inserted with alternative text to represent concepts and information without lengthy descriptions.

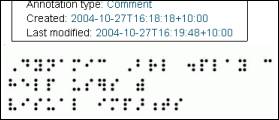

On other occasions, John can choose to display information in a different form or modality. For example, a Braille version of text may be necessary for blind users (example of this sentence shown below). In this case, John would use braille translation software and a braille embosser to make a braille (tactile) version of the material.

Maria is delighted with the annotations John has made for her. Maria decides to use Amaya to make annotations for her research and assignments. But is troubled by the following question;

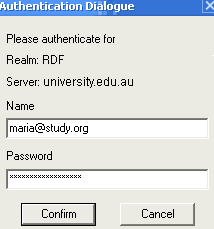

Can other people using Amaya access annotations that I have made?

The answer to this is no. The Annotea server manages the annotations made by Amaya including managing user information and access [4], so Maria can create her own personal account with her individual username and password. When Maria tries to save an annotation, she will be prompted to provide access authentication.

Luke is a good friend of Maria's. He has previously studied the same subject. Maria, working on her final big project, asks Luke if he can help by proof reading her existing annotations and suggest new viewpoints/arguments. Luke is glad to help but does not want to change the original state of any annotations Maria has made. Annotea has the capability to allow Luke to create annotations for existing annotations.

The example above shows Luke's annotation of Maria's assignment structure. Amaya has a number of attributes that give Luke formatting options. He also adds a hypertext link to an external resource using Amaya's toolbar.

The facility to annotate and make annotations of annotations offers flexibility and can be used as easily by someone, for example, wanting to mark where they need additional help.

The Quinkan Culture Matchbox is a system for cataloguing Aboriginal culture from the Laura reserves located in far north Queensland (Australia) [15"] [12]. The reserves contain a rich collection of rock art paintings dating back tens of thousands of years. Aboriginal Elders of the community are involved with project members in managing the preservation of cultural knowledge in the digital repository. Elders use storytelling to educate the younger generation about spirituality, heritage, historical events, ancestral places and objects. Some information is sacred and is only told to certain members of the community [16]. For these reasons, interpretations of cultural material may differ among tribes. Accessibility, when dealing with cultural information is very important. The Canadian Network for Inclusive Cultural Exchange (CNICE) recognises this and has developed guidelines for publishing online cultural information [17].

A number of different users may use Matchbox including students, researchers, archaeologists, anthropologists, cataloguers and others. Amaya can be used to combine accessibility with multicultural, multilingual cultural information to enrich the communication of knowledge. (It is important to note that due to traditional customary laws, interpretations of cultural objects in the Quinkan Region can only be made with authority and permission of community Elders [12].)

Kathy is an archaeologist cataloguing cultural interpretations of rock art paintings, She asks a Laura community Aboriginal Elder for his viewpoint. An Aboriginal Elder can usually understand a number of languages and may have English as a fith or sixth language. He may have trouble reading and writing in English. Oral expression is often the best mode of expression [12]. Kathy uses Amaya to annotate resources using video, diagrams and transcripts to express interpretations.

As mentioned earlier, interpretations can be kept private through authorisation in Annotea. Using Amaya in a cultural context can create multiple pathways for those seeking relevant information; a user at a museum could customize their search so that resources annotated by archaeologists are of higher relevance.

This paper presents scenarios to demonstrate free tools provided by the W3C being used to supplement content for people with special needs and preferences. Different versions of existing inaccessible resources are customised, based on user needs and preferences, to provide for richer understanding of those resources. The provision of improved accessibility for people with disabilities, whether they are the result of cultural background, lack of literacy, poor education or physical circumstances, especially to resources over which the user or local provider has no control, can be achieved in a number of ways. Using Semantic Web technology, as described above, is only one way but often worth the effort.

1.Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), [cited September 28, 2004]. Available from http://www.w3.org/WAI/.

2. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2004 [cited September 28, 2004]. Available from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/c258c88a7aa5a87eca2568a9001393e8?OpenDocument.

3. Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1992 Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, [cited October 2, 2004]. Available from http://www.hreoc.gov.au/.

4. W3C Annotea Project World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), [cited September 28, 2004]. Available from http://www.w3.org/2001/Annotea/.

5. Amaya: W3C's Editor/Browser World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), [cited September 28, 2004]. Available from http://www.w3.org/Amaya/.

6. Annozilla (Annotea on Mozilla) Mozilla software development community, [cited September 29, 2004]. Available from http://annozilla.mozdev.org/.

7. Annogates - an Annotea client for Internet Explorer Annogates, [cited 2004, October 1]. Available from http://www.formatvorlage.de/experiment/annotea/.

8. Zope Server Zope Community, [cited 2004, October 2]. Available from http://www.zope.org/.

9. SWAP - The Semantic Web Accessibility Platform UB Access, [cited September 9, 2004]. Available from http://www.ubaccess.com/swap.html.

10. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 W3C Working Draft 30 July 2004, [cited 2004, October 2]. Available from http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/WD-WCAG20-20040730/.

11. Babel Fish Translation Altavista, [cited September 2, 2004]. Available from http://world.altavista.com/.

12. Nevile, L., et al. Rich experiences for all participants. in Museums and the Web 2004. 2004.

13. TILE: The Inclusive Learning Exchange Adaptive Technology Resource Centre, [cited September 3, 2004].

14. Designing web pages for dyslexic readersDyslexia Parent, [cited September 3, 2004]. Available from http://www.dyslexia-parent.com/.

15. Lissonnet, S. and L. Nevile. Quinkan Matchbox Project: challenges in developing a metadata application profile (MAP) for an indigenous culture. in AusWeb. 2003.

16. Indigenous Australia: Family Australian Museum, [cited September 9, 2004]. Available from http://www.dreamtime.net.au/indigenous/family.cfm.

17. Canadian Network for Inclusive Cultural Exchange (CNICE) The Adaptive Technology Resource Centre, University of Toronto, Canada, [cited September 11, 2004]. Available from http://www.utoronto.ca/atrc/.

18. Australian Research Council (ARC) Quinkan Matchbox site Matchbox Project, [cited September 8, 2004]. Available from http://www.jcu.edu.au/rockart/.

1 Please note that this example is for demonstration only and the translation may not be accurate.